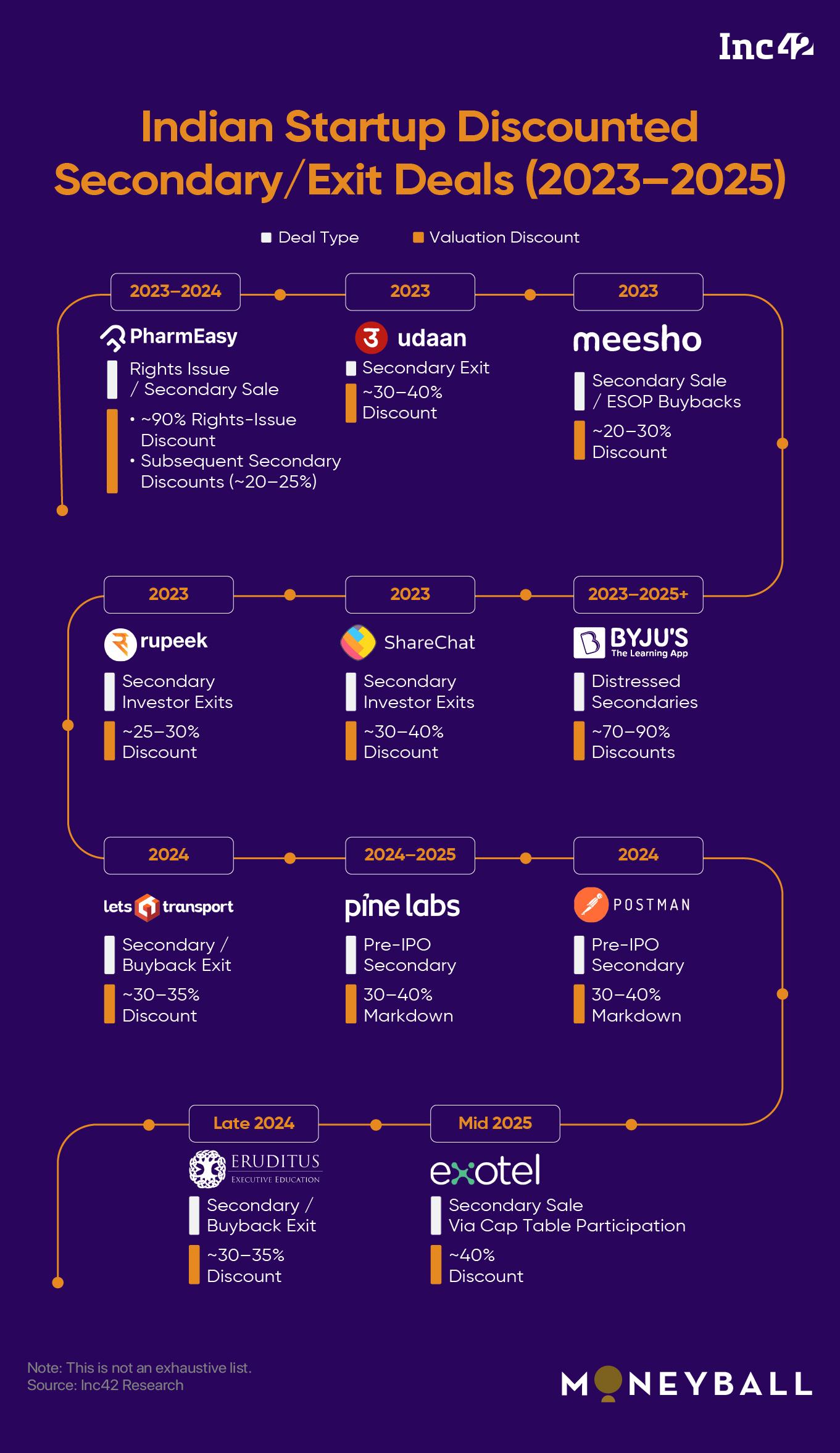

When Catamaran Ventures’ President, Deepak Padaki, recently observed that loss-making companies are seeing secondary sales at a 30–40% discount, it may have seemed to many like a new phenomena. But this is the reality for the Indian startup ecosystem since late 2023: VC exits with big discounts on the valuation.

Startups without clear paths to profitability have all gone through a valuation reset, with discounted exits becoming increasingly common in growth and late-stage deals.

Investors told Inc42 that the frequency of discounted transactions has risen over the past few years, pointing to cases such as Eruditus, Postman, and Exotel, which saw secondary sales at 20–40% markdowns between late 2023 and mid-2025.

Although startups that endured the difficult years from late 2022 to 2025 have largely stabilised, focussing on sustainability over growth and even planning IPOs. Distress sales, where companies are sold because there is no path forward, have become somewhat rarer.

Most discounts today occur in secondary transactions driven by funds nearing closure or holding large stakes. In some cases, investors sell early — even ahead of IPOs — to secure partial exits.

But the steepest corrections are happening in companies that prioritised scale and optics over fundamentals.

Sagar Nishar, CIO of Aarii Ventures, the investment office of the Kothari family, highlighted that investors are no longer rewarding narratives. They are examining governance, margin stability, and customer retention more deeply. Some buyers are passing on even 40% discounted rounds when fundamentals do not hold as the mindset has shifted from “cheap is attractive” to “defensible is attractive.”

An example he cited is of a consumer brand (name not revealed), which pursued aggressive expansion and gained nationwide recognition in 2024 through branding and celebrity endorsements, but mismanaged costs and lost key team members, resulting in a 50% drop in valuation.

Or a deeptech venture (again undisclosed) with long R&D cycles exited at less than half its peak valuation. These companies were backed when funding was flowing freely, but now VC firms are looking to exit their positions as their funds expire.

It’s not just deeptech, but even edtech, aspirational retail chains, B2C fintech apps have faced steep cuts as customer acquisition costs outpaced retention.

“We have observed that companies experimenting with scaling or untested business models faced sharper adjustments, while industrial, frontier tech, and regulated sectors largely maintained valuations. Overall, around 6-8% of exits we tracked in the last year happened at a discount, showing that corrections are selective rather than uniform,” added Nishar.

On a similar note, Abhishek Prasad, managing partner at Cornerstone Ventures, an enterprise SaaS fund focussed on early growth-stage startups, noted that in the commerce ecosystem — spanning B2C, B2B, and retail — corrections have largely played out, leaving the space more streamlined. He added that sectors like distribution, logistics, and healthcare are relatively stable, as their opportunities were never overstated or oversold.

Still, not all trends are positive. Nishar observed that distress-led sales are likely to persist over the next year, particularly among companies weighed down by high fixed costs or unsustainable marketing spends.

“By 18-24 months, we expect a bifurcated market: disciplined, cash-generating businesses will command premiums again, while visibility first ventures will continue to see markdowns or consolidation,” said Nishar.

Discounted Exits: Cause For Concern Or Market Normalisation

Discounted Exits: Cause For Concern Or Market Normalisation Anup Jain, founding partner at BlueGreen Ventures, an early-stage VC fund focussed on fuelling growth across transformative sectors, believes the perception of caution around secondary transactions is overstated. In his view, founders and investors have recognised that accepting a 20–30% discount in secondary markets today is often preferable to waiting for an IPO that may enforce the same correction later.

In fact, these discounts don’t always imply structural weakness in the underlying companies, notes Pranav Pai, founding partner and chief investment officer at 3one4 Capital, an early-stage, sector-agnostic venture capital firm. He further highlights an uptick in structured exit mechanisms, such as GP-led continuation vehicles. In these, a blended discount is applied across a portfolio to provide liquidity.

“This is already routine in mature markets like the US, and its emergence in India signals increasing market depth and institutionalisation. In India, highly competitive rounds in sectors like consumer, fintech, and software have routinely seen valuations pushed higher as multiple investors bid for the same deals,” Pai added.

Cornerstone’s Prasad further noted that his firm follows a hybrid strategy, with 30% allocated to late-stage investments, typically secondaries in companies that are two to three years from IPO.

“So, for us, I feel the negative sentiment is misplaced. It’s just about timing. Overall, the momentum is positive. This is a past hangover. This is the challenge, and I guess the biggest caution to keep in mind is that this should not be repeated. We are doing exaggerated value to get into deals,” added Prasad.

Even the latest funding numbers indicate positive momentum. According to Inc42 data, in 2024, the Indian tech startup ecosystem saw over 1,900 active investors, investing approximately $12 Bn+. Investor participation increased by 23% compared to 2023, while the total funding grew by 20% from $10 Bn in 2023. At the same time, more than 84 new startup funds worth $8.7 Bn were launched, with the value of funds growing by over 55% year on year.

Despite the positive momentum, a segment of the investor ecosystem remains skeptical and advocates caution. The following are some key factors contributing to startup exits at a discount in the current scenario:

Lack of Opacity & Transparency In VC EcosystemSEBI introduced regulations for the venture capital ecosystem in 2012, providing a formal framework for domestic funds to operate. The first domestic VC funds emerged in 2013, but it took two to three years for many firms to successfully raise capital. In those early years, fund sizes were relatively modest, typically ranging between INR 100 – 300 Cr.

BlueGreen Ventures’ Jain raised a pertinent point. The hallmark of any industry is performance. In the financial services world, mutual funds in the public market receive ratings daily. But when is the performance of venture capital funds assessed? Typically, it happens mid-tenure, when they report a paper IRR, NAV, or distributions. However, in the first phase of the ecosystem, the funds of 2013–14 did not do that. The paper performance itself has been highly opaque.

Although industry reports and benchmarks come out, participation is patchy. Some people respond, some do not. For example, most industry reports clearly state that its data is only based on those who responded.

“That means a whole lot of people did not respond, so how can it represent the industry? Similarly, Crystal and other reports rely on voluntary data, because SEBI has not made it mandatory for funds to submit data or follow any uniform method of calculating IRRs,” added Jain.

There is also no standard method to evaluate the performance of a venture capital fund. Each fund reports differently — some show IRRs as of their last funding round, while others report them as of today. If an LP is promised a hurdle rate of 12% per year, the IRR should be adjusted or rolled back accordingly when no new funding round occurs. Instead, the clock is often stopped, which inflates IRRs beyond reality.

“Because of this opacity and lack of transparency, nobody knows the real performance of any fund. LPs won’t speak, and their identities are confidential. So, the system is bottled and shut. It favours the players, not transparency, not investors, and not those trying to enter the ecosystem. What is shared publicly is selective good news. One investment doing 20x does not mean the entire fund has done 20x,” said Jain.

He even highlighted that today, 12 years later, after multiple extensions — and SEBI granting further extensions through lobbying by bodies like the Indian Venture Capital Association — funds from 2013 are still active. Their IRRs are unknown, their distributions are unknown.

New funds and incoming investors, therefore, have inadequate data. They rely on introductions and personal warmth from LPs who may praise a fund manager because they like them, not necessarily because of performance. Decisions are being made in the dark, on the basis of incomplete and inadequate information, often with caveats and footnotes attached.

Larger Funds Under Pressure As Term EndsIf a fund life, which is typically 8-10 years, is coming to an end, then as per SEBI’s mandate, they have to close, as at the end of the day, the main goal is to return money to the LPs from whom the fund was raised.

Here, family offices can take a longer view and provide bridge capital when cycles misalign with a company’s trajectory. Smaller and mid-sized funds, meanwhile, can remain disciplined at the entry point. For most of the ecosystem, this approach helps avoid getting stuck in such situations. However, with the larger funds the situation is very different.

“The challenge as the industry scales is that there are several very large funds. If you are a $5 Bn fund, for instance, and you need to generate a 3x return in 10 years, then with an average ownership of 20% in a company, that company must be valued at around $75 Bn,” said Prasad.

Let’s understand this. Right now, India has about 120 unicorns. Most are valued around $1 Bn, with only a handful at $2 Bn, $3 Bn, or $5 Bn. This means that out of 120 unicorns, at least 70–75 would need to scale to much higher levels for large VC funds to get the desired outcomes.

That forces VCs to do whatever it takes to get into these companies — writing large cheques, offering high valuations, and sometimes investing even without metrics. This pushes valuations up and creates distortions in the ecosystem aka a bubble.

But all that changes towards the end of the fund cycle; there have been cases of GPs and fund managers agreeing to discounted secondary sales, even when the company has a strong operational outlook, simply to show the DPI.

When asked whether fund managers face pressure from LPs for exits apart from fund timelines, Prasad explained that this depends on the stage at which the fund operates. If a fund went in at Series A or Series B, and is now selling at the end of fund life, then it’s possibly already sitting on a 20x multiple and probably be selling at a 15x, which is giving a 25% discount.

“But you still made 15x, so LPs are happy. More important than the multiple is always this — when LPs, instead of waiting for three years to get this cash flow, are actually getting it today itself, and that kind of protects the IRR of the investment,” added Prasad.

But the wrong decisions between the aggressive years of 2020 to 2022 have caused some pain.

Mismatch Between Visibility And Economics“We’ve seen a lot of these late-stage funds completely not investing at all, sitting on the fence and not taking decisions, because their LPs have come down hard. Investment committees have told them that unless this mess gets fixed up, you should not be doing anything,” he added.

Many consumer-facing fintech and retail ventures that scaled rapidly between 2021 and 2023 on the back of VC money struggled to turn this acquired engagement into sustainable cash flow. Over-reliance on marketing and ads as well as high salary expenses skewed this further.

Fund life cycles and internal shareholder misalignments add pressure, but the trigger is usually operational fragility rather than pure market slowdown, said Nishar.

The real test lies in how the public market treats these companies when they go for IPOs. Without the right business metrics to justify valuations, IPOs either fail or struggle to find underwriters, and this has contributed to some of the investor anxiety around secondaries.

Can AI Wave End The Discounts?Prasad added: “The need of the hour is to swallow the bitter pill, acknowledge that some companies were overvalued, close a few deals at the right valuations, take the hit, and move forward. That’s the challenge — an unmatchable challenge of a scaling industry.”

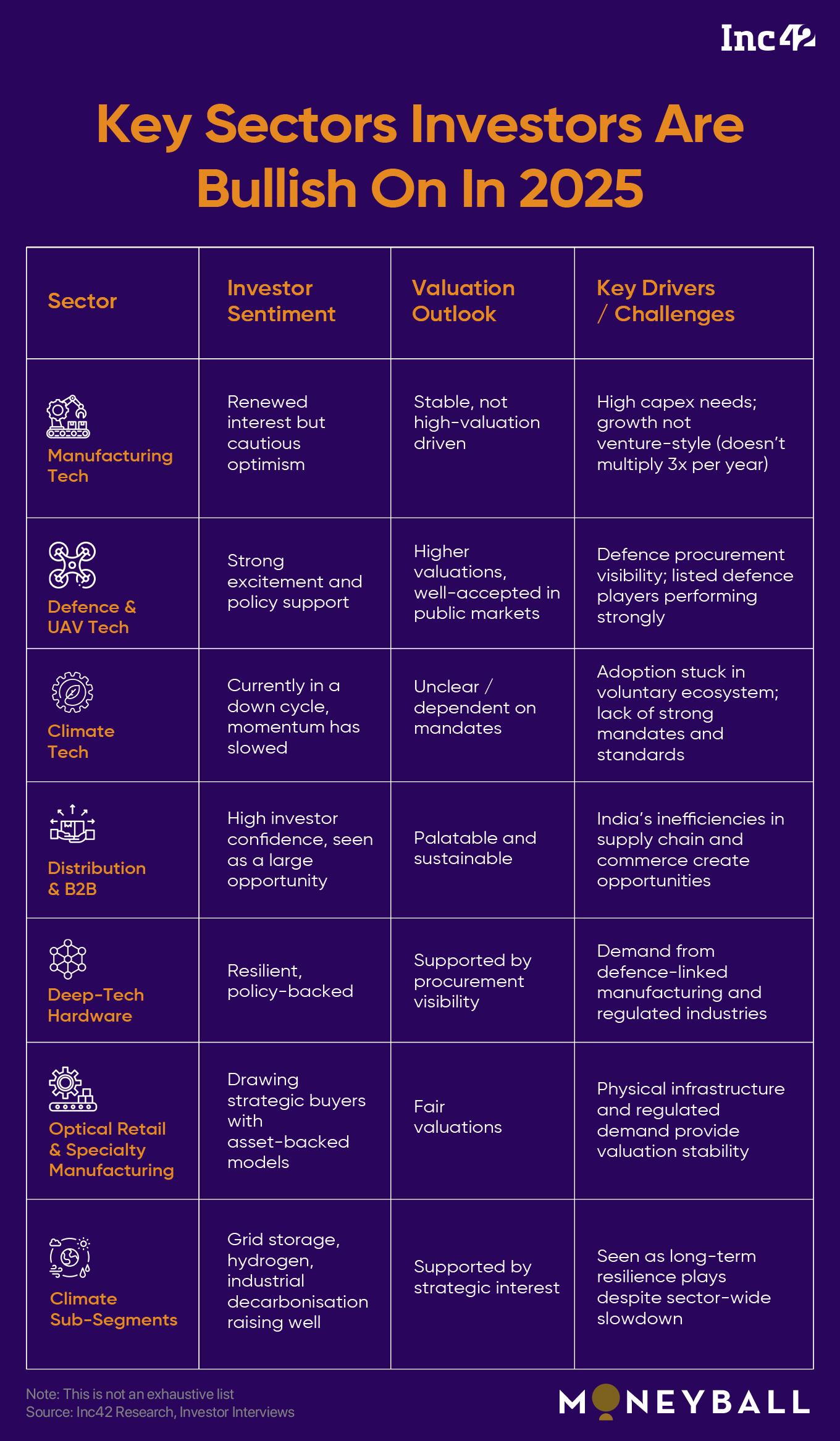

As 3one4 Capital’s Pai, noted, unlike the US, India hasn’t yet entered an AI-only hype cycle. Here, the opportunity set is broader — manufacturing, semiconductors, deep tech, consumer, and fintech are all attracting capital and holding valuations. This is more a reflection of the quality of the breakout companies in these sectors, rather than simple tailwinds from sectoral interest.

“With India expected to add $4 Tn to its GDP over the next decade, the most significant expansion of opportunities to date will span multiple sectors rather than being concentrated in areas like AI alone. Hundreds of companies are likely to move towards late-stage and IPO-driven expansion rounds. In this context, discounted secondaries should be seen as a normal tactical aspect of private markets as exits become more routine,” added Pai.

Since AI is not a winner-take-all space. Building a foundational model is highly challenging and capital-intensive, but companies operating in the orchestration or solutioning layer have a more solid footing. With reasonable commercial acceptance, this can be a strong entry point into the AI ecosystem.

Also, it is now a clear fact that AI only unlocks value when applied to mission critical problems, not as a cosmetic layer. Generic productivity tools without clear IP are finding it much harder. The bifurcation is stark between “AI for optics” and “AI as infrastructure.”

While AI continues to attract significant global excitement, valuations are often higher than they should be. As Cornerstone’s Prasad highlighted, ideally, anything upwards of 10x or 12x revenue multiples is outrageous, simply because there is no real visibility yet on what profitability will look like.

“We have seen companies in the AI space going at 15x or 20x multiples, which is out of whack. Anything around 6x or 7x is a more reasonable multiple to work with, though such deals are rare. Many companies are still to prove commercial acceptance, which is why some of them may end up being overpriced,” added Prasad.

Is Exit Still A Dream In India?

Is Exit Still A Dream In India? Venture capital in India has now crossed two decades, marked by distinct phases of growth and challenges. The first decade, from 2005 to 2015, was driven largely by the consumption story.

Ecommerce and B2C ventures took centre stage, giving rise to India’s first unicorns. But much of the capital then was external, and with no clear exit pathways, investors were unsure of how value would eventually be realised. The turning point came with Walmart’s acquisition of Flipkart, which proved that large-scale exits were possible and delivered significant returns to early backers.

Not much has moved the needle since then.

At the ecosystem level, there is a structural shift underway. A strong base of domestic venture funds has matured, with several raising second, third, or even fifth funds for India. Unlike the short-term global entrants, these mid-sized funds bring consistency, experience, and a deeper understanding of cycles. The supply of such capital signals a healthier and more resilient venture environment than what existed a decade ago.

Against this backdrop, exits in India may not be an elusive dream anymore. With M&A activity, IPO pipelines, and a maturing venture landscape, the building blocks for a sustainable exit environment are finally in place—even if the timelines remain uncertain.

The post India’s VC Exit Puzzle: Valuations Fall, Secondaries Rise appeared first on Inc42 Media.

You may also like

Doorbell footage captures delivery driver's 'hilarious' answer to Taylor Swift question

'Rahul Gandhi fit only for sitting in Oppn': Pralhad Joshi's reaction to Cong claims on GST reforms

Great step towards Aatmanirbhar Bharat: Maha, Gujarat dairy traders welcome GST 2.0 reforms

Punjab: CM Mann announces appointment of one gazetted officer for each village

North Korea's Kim holds talks with China's Xi in Beijing: Reports